Synopsis:

At approximately 7am on Wednesday, February 3, 2021, a NH Fish and Game officer contacted the lead snow ranger at the USFS Mount Washington Avalanche Center to ask for assistance in locating the vehicle of an individual who was reported missing on Tuesday night, Ian Forgays, a 54 year old male from Vermont. Recent communications between Ian and his friends suggested that he had been planning a day of backcountry skiing, either in Ammonoosuc Ravine or Monroe Brook on the west side of Mount Washington, on Monday, Feb. 1, prior to the start of a significant winter storm arriving Monday night and continuing Tuesday. At 10am on Wednesday, searchers found Ian’s car at the Ammonoosuc Ravine Trailhead parking lot; by 4:25pm, an avalanche beacon signal was found deep in a debris pile of an avalanche. By 6pm, Ian was found dead, 13’ down in the debris pile. The autopsy identified asphyxia as the cause of death.

Rescue and Recovery Effort:

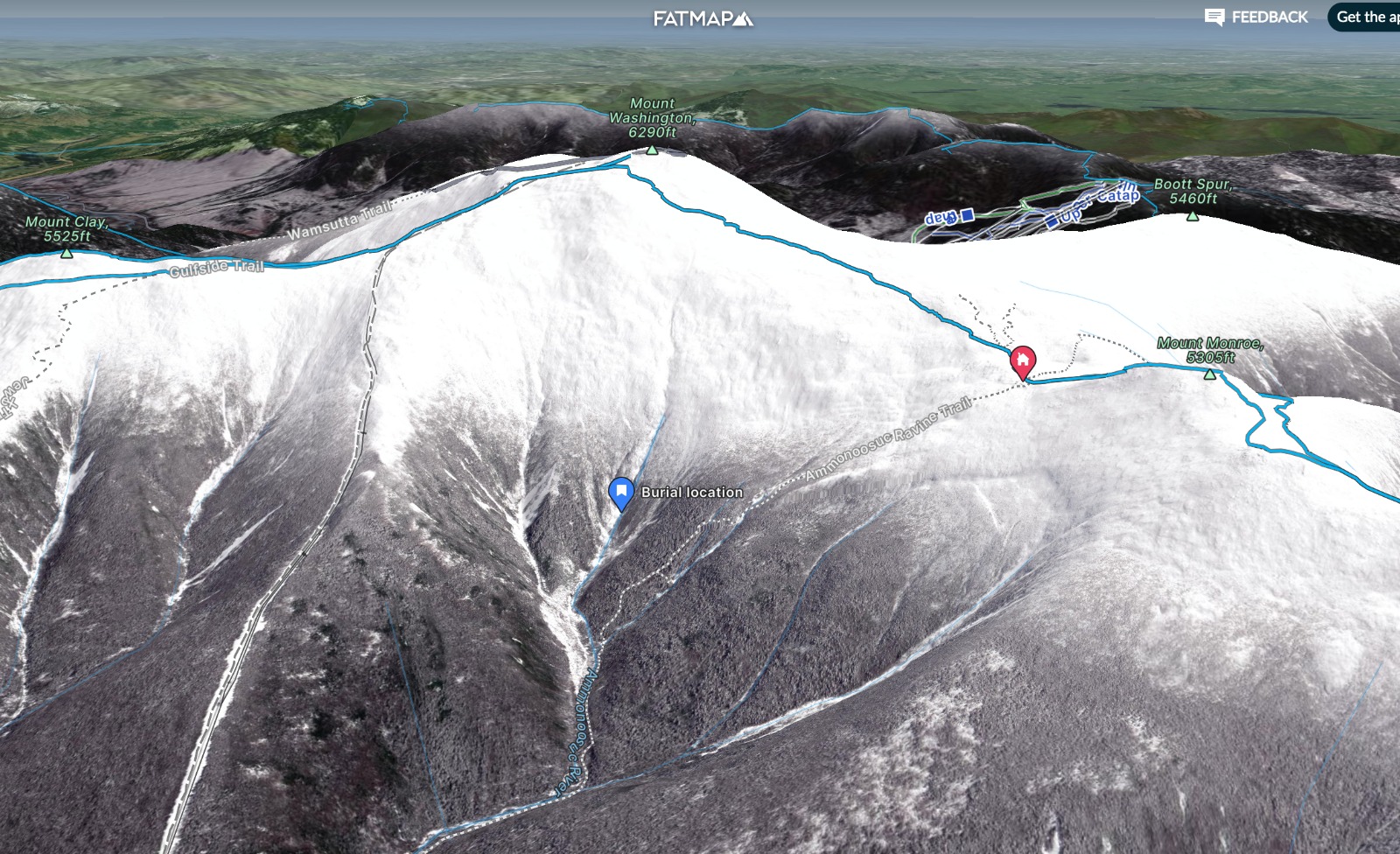

Ian Forgays was reported missing Tuesday evening, almost 24 hours after he would have completed his ski tour. Friends called to report the situation to NH State Police who then used cell phone telemetry to confirm the subject’s general whereabouts. Cell phone towers in Littleton, NH on the west side of the range, and in Jackson, on the east side of the range, had received “pings” from the subject’s phone on Monday afternoon, somewhere in the vicinity of Mount Monroe. By Tuesday evening, with sparse information to go on, it was thought that the skier may have changed plans, thus triggering a search of parking lots on both the East and West sides of Mount Washington. In the heavy snow that resulted from the storm beginning Monday night, the more distant, unplowed Ammonoosuc Ravine (a.k.a. “the Ammo”) Trailhead parking lot was not checked. Having a confirmed parking location would narrow the search area; without that information, a ground search could not commence on Tuesday.

The following morning, NH Fish and Game duty officers resumed searching for the subject’s vehicle. At 9:54am, the missing skier’s vehicle was found in the Ammonoosuc Ravine Trailhead parking lot. Shortly thereafter, a ground search was organized while team leaders analyzed a series of the subject’s photos and texts to friends and were able to produce a likely timeline of events that helped focus efforts on the area surrounding Ammonoosuc Ravine. Avalanche hazard on Wednesday morning was forecast as Considerable following High danger the previous day. Light freezing rain and snow showers were falling at higher elevations in the search area. Small teams of three or four were sent to likely locations including Monroe Brook, Ammonoosuc Ravine Trail, and three of the drainages that make up the headwaters of the Ammonoosuc River. Open water and thinly bridged stream crossings, combined with elevated avalanche danger, forced teams to travel through dense brush along stream banks. Deep snow created “spruce traps,” hindering rescuers’ travel, even wearing skis and snowshoes.

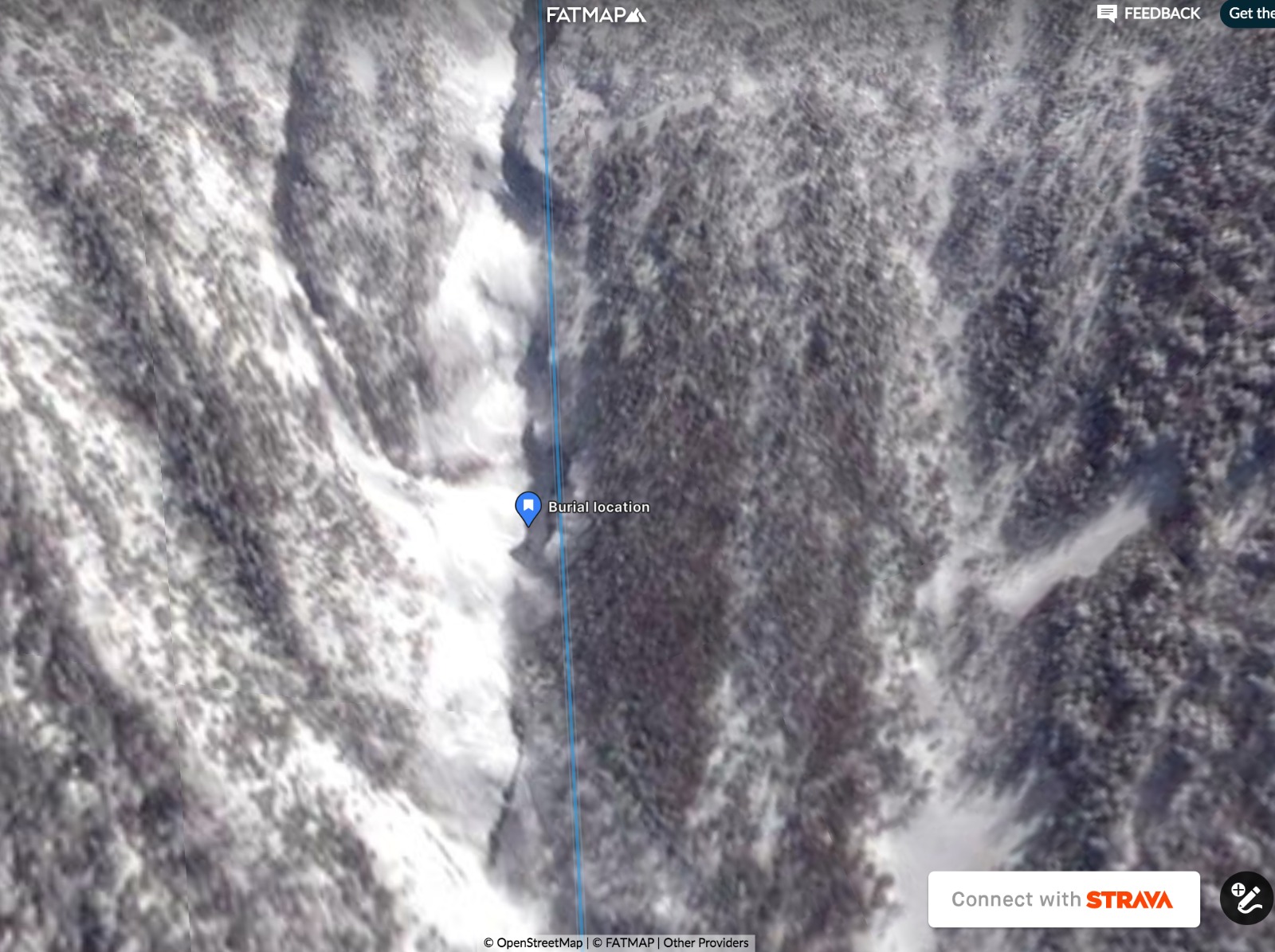

The cliff band that forms the right side of the terrain trap is clearly visible to the right of the burial location.

By early afternoon, advanced cell phone forensics narrowed the last known point of the subject’s cell phone to an area almost directly above the main drainage of the Ammonoosuc. Around the same time, two skiers exiting Monroe Brook, also members of another local rescue team, reported hard snow and no avalanche debris in the Monroe Brook slide path. Search teams then shifted attention to the two drainages closest to the main Ammonoosuc ski line as daylight began to wane.

As searchers left the hiking trail and made their way up the drainage, they checked deep pools of water beneath steep pitches of snow for signs of the subject. As the team pushed farther into the Ammonoosuc slide path, debris and some broken small trees were evidence of recent slide activity, most likely from a widespread avalanche cycle the previous day (Tuesday, one day after the subject skied the area on Monday). One small team split up to search the main gully of the Ammonoosuc and the looker’s right fork, as other teams arrived after searching other zones. Both gullies showed evidence of chunky, fresh avalanche debris with broken bushes mixed in. At 4:25, a beacon signal was acquired by a searcher with a dog and Recco receiver in the uppermost flat area beneath the largest continuous WNW-facing slope of the Ammonoosuc, at around 3950’ of elevation. Pinpoint search techniques with an avalanche transceiver located a beacon signal 3.8 meters (12’6”) beneath the debris, which had piled up against the face of an overhanging rock buttress.

Another rescuer soon arrived and one began to probe while the other removed snow from the surface to enable the longest available avalanche probe (320cm) to reach the victim. As more rescuers arrived and lowered the grade of the snow by more than a meter, a probe strike was finally confirmed and digging continued. Eight rescuers took turns digging for an hour and thirty five minutes, when they reached the victim’s body.

Another 45 minutes of digging was required to fully extricate and then move the victim up the snow platforms that had been dug to access the bottom of the hole. Snow anchors and rope belays were then established to lower the victim over two pitches of steep snow and ice. The victim was then packaged in a stiff plastic rescue litter (SKED) and transported 1.7 miles to the trailhead. Along the way, the team was challenged to avoid open water and the thin snowpack over the riverbed while finding a route to rejoin the Ammonoosuc Ravine Trail. The rescue party reached the trailhead at 8:45pm and transferred custody of the body to the Assistant Deputy Medical Examiner.

-Frank Carus, Lead Snow Ranger

A rescuer begins to probe just after a Recco and beacon search found a signal 4 meters beneath the snow. The avalanche path is the narrow strip of snow in the background, between the ice on the left and the boulders on the right.

Analysis:

Information provided by the missing subject’s friends was critical in piecing together a search plan that would include the areas with the highest probability of detection. The heavy snowfall on Monday night and high winds Tuesday erased any foot or ski tracks along with any hope of an aerial search, even if the weather was clear enough to allow a flight. Texts to the subject’s friends stated that Forgays had planned to “take advantage of low avy danger and low winds up high” prior to the onset of a significant winter storm set to arrive Monday night. By 9am on Monday, the skier had reached treeline on Mount Monroe, and by 11am he was near the summit of Mount Washington. Recent observations submitted to the Mount Washington Avalanche Center confirmed a general lack of snow at upper elevations of Mount Monroe and around Lakes of the Clouds. (Observations of this area are often more limited in number due to much lower usage levels there.)

View past Lakes of the Clouds hut towards the Ammonoosuc, sent from the victim’s phone shortly before he skied into the Ammonoosuc Ravine.

The first avalanche:

On Monday, 2/1/2021, the day that the subject went skiing, the level of avalanche danger for the area was rated as Low. Conditions included a mix of snow surfaces ranging from ice to rimed snow to firm wind slabs, all of which are commonplace in the wind-raked high alpine areas and steep ravines. Snow surfaces and layers beneath included a widespread, wind-hammered surface created by a wind event the week before. It was dubbed the “157 Layer” after the 157-mph peak wind speed on January 24th which helped create it. Above that layer was another softer wind slab layer that was described in the forecast as

“…smooth, hollow sounding slabs (that) are easy to identify and are generally worth avoiding due to low skiing quality and postholing on foot if not due to the elevated avalanche risk.”

This is most likely the wind slab that the victim triggered.

The Bottom Line portion of the forecast stated:

“the potential for small avalanches of wind drifted snow remains in isolated areas at mid and upper elevations.”

There are sometimes days when a low avalanche danger rating appears to counter a classic admonition that avalanche educators use: “low danger doesn’t mean no danger”. Conditions with essentially no real avalanche danger can, in fact, exist – for example, isothermal spring snow or rain events followed by a deep freeze. Monday, February 1 was not that kind of day. Information provided by family and friends indicates that Forgays had skied Mt Washington hundreds of times and had extensive knowledge of the varying conditions on the mountain. A skier of Forgays’s talent and experience, and many other skiers, would likely have considered the conditions on that day to be variable and challenging which is par for the course for skiing in the Presidential Range in mid-winter. His choice to ski that day seems informed and intentional, and his past ski missions with friends reflected an enthusiasm for any sort of skiing adventure. A text to Forgays’s friend on Sunday said he “might ski Monroe Brook depending on how the Ammo looks”.

The avalanche problem on February 1 listed some “examples of the isolated areas where wind slabs exist”. Prior photos of the Ammonoosuc terrain show expanses of ice cliffs and icy rock slabs, all of which break up expanses of snow, leaving isolated areas of bed surface, along with steep sections and lower-angled catchments for slabs to accumulate. A photo sent by Forgays that day of the Ammonoosuc Main Gully showed the skiing conditions were indeed “technical”.

Forgays took this photo on his way up the Ammonoosuc Ravine Trail. A ridge to the right of the Main Gully obscures the steepest sections of the line.

Southerly winds on Friday the 29th built wind slabs on northerly aspects with just one confirmed natural avalanche (small D2) which occurred overnight.

This photo of Left Gully was one of the examples listed as a wind slab that could be found in isolated areas. This one varied in density (from 4F+ to 1F) across the surface over softer snow (4F to fist) beneath and was about 12-16” thick.

It is likely that Forgays triggered one of these pockets and was carried into the bowl-like depression, where the snow was stopped by an overhanging cliff that was angled upslope. The debris pile here was deep, but fairly narrow, fanning out from a 10’ strip to about 25’ wide by 40’ long. The flat area that created the terrain trap was not fully covered by debris, even following the natural avalanche cycle that followed the next day. A second avalanche is further supported by the widespread avalanche debris throughout Tuckerman and Huntington Ravines observed on Wednesday. Debris piles from avalanches in paths adjacent to the accident site were also observed during the recovery effort.

The conditions late Monday and into Tuesday, after Forgays triggered the smaller avalanche, brought 12-14” more snow to the east side of Mt Washington, 4” to the summit, along with a ten-hour period of 70-100 mph winds from the east. Wind driven snow drifts into thick slabs that exceed the carrying capacity of the soft snow below. The weak layer fails and the slab slides to the bottom of the slopes. High winds and significant snowfall are the conditions that are more likely to produce a 13’ deep burial. The week prior to Forgays’s burial only brought four inches of snow total to the summit with much lower wind speeds. The cold nights and some wind loading did create wind slabs, but they were relatively small in size.

An examination of the crown of the Forgays avalanche wasn’t possible since extreme winds and new snow that fell the following day erased all the signs. Weather factors and observations from other areas suggest a small (D1 – see page end) wind slab was most likely. However cold temperatures and a thin snowpack on the west side could have also led to an avalanche on a faceted weak layer around one of the crusts such as the January 16 crust. The thinner snowpack on the west side supports this though no other avalanches were reported on this layer. A profile of the debris did not show any discernible harder chunks that would have been more suggestive of a larger avalanche involving all of the snow above the rain crust (the Christmas rain crust) formed in late December. Since, the 157 mph hard slab layer formed on top of both of the crusts, hard chunks of that layer would have been noted in the pile. Again, the evidence points to a small wind slab among the slabs of rock and ice on his intended run.

Rescuers digging down to enable an avalanche probe to reach and precisely locate Forgays. Note the narrow strip of debris adjacent to the rocks with no debris to the left of the rescuers.

The second avalanche on Tuesday following Monday’s fatal avalanche:

Monday’s forecast referenced what was coming on Tuesday:

“Much of the western aspect of the range has limited snow coverage but there are plenty of areas large enough to produce a large (D2) to very large (D3) avalanche with the incoming snow. Think Oakes Gulf and the Ammo as falling into the latter category.”

Until this event on February 2, the Ammonoosuc and West side of Mount Washington had minimal snow coverage, as it does most years. East winds and heavy snow are needed to really fill in the terrain in the Ammonoosuc Ravine. A Nor’easter on January 16th, with necessary east winds and heavy snow, improved the coverage, though many ice flows, boulders and patches of old crusts appear in the most recent photos. Unstable weather from the 23rd through the 29th brought 3.4” snow to the summit and 8” new snow to the Hermit Lake snowplot, on the east side of the range, resulting in some degree of forecast uncertainty along with the typical spatial variability of our typical wind slab avalanche problem. Scoured surfaces, firm and stubborn wind slabs, more reactive wind slabs and partially buried crusts peppered middle and upper elevations, especially on the windward east side. Despite, or perhaps because of, these technical skiing conditions, many folks are drawn to the West side of Mt. Washington, especially those travelling from Vermont and points West. Lower use in this area also promises more adventure, with fewer concerns due to crowding than the vastly more popular east side.

Accidents like this serve as a stark reminder to us all of the role that luck can play in successful outcomes in our backcountry endeavors. Ian Forgays had many years of experience in this terrain and, according to texts sent on Sunday, planned “to move slowly and intentionally” knowing that some lines there are “rowdier than others”. By all accounts, he was a very accomplished skier with many of the steepest lines in the Whites under his belt. Finding a triggerable slab in mostly safe avalanche conditions is rare but not unheard of, especially due to our spatially variable, wind slab avalanche problem. Accurately assessing snow and terrain and avoiding trouble throughout a lifetime of playing in the mountains is a tremendous challenge for anyone, even for the most experienced, like Forgays. Most of the time, we survive to ski another day. Other times, simple bad luck catches up to us when our margin for error disappears.

In this case, when Ian Forgays triggered a small wind slab, a partner may have saved his life…but given the terrible terrain trap below, maybe not. Forgays was found equipped with avalanche safety gear, including an avalanche transceiver, which helped rescuers and the family immensely. It appears evident from the totality of the circumstances that Forgays was prepared and knowledgeable about the mountain and its ski conditions. But, it is important to remember that even the most experienced skiers with all the correct preparations and equipment risk more when skiing alone. Even small avalanches can be deadly, especially over a terrain trap. If there are lessons to be learned from this accident, they aren’t new. Skiing technical lines, in a thin snowpack above a notorious terrain trap, with no partners, even on a Low danger day, raises the stakes tremendously.

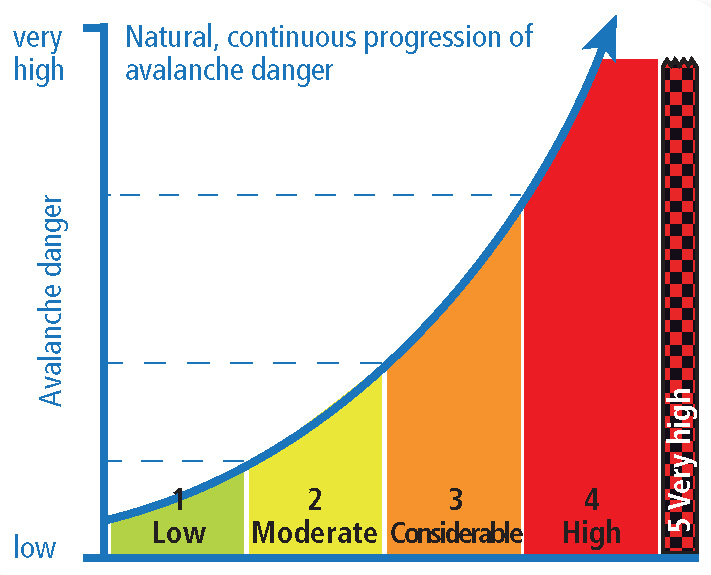

AVALANCHE SIZE

D1 refers to the destructive power of an avalanche. A D1 is relatively harmless, D5 is an historic avalanche that can gouge landscape. D1 are considered small avalanches but are known to be able to bury a person in a terrain trap or push a person off a cliff. The mass of avalanches that the scale represents is exponential. It is important to remember that the avalanche danger rating scale, like the destructive scale of avalanches, is also exponential. The ratings exist along a continuum of growth with the danger at the high end of one rating being exponentially higher than the danger found at the lower end of that same rating.