Type: Hard Slab

Trigger: Artificial, Skier

Size – Relative to Path: R3

Size – Destructive Force: D2

Slope Aspect: Southeast

Start Zone Elevation: 5000

Average Slope Angle: 40 degrees

Slope Character: Convexity in Sluice Gully

Summary Description

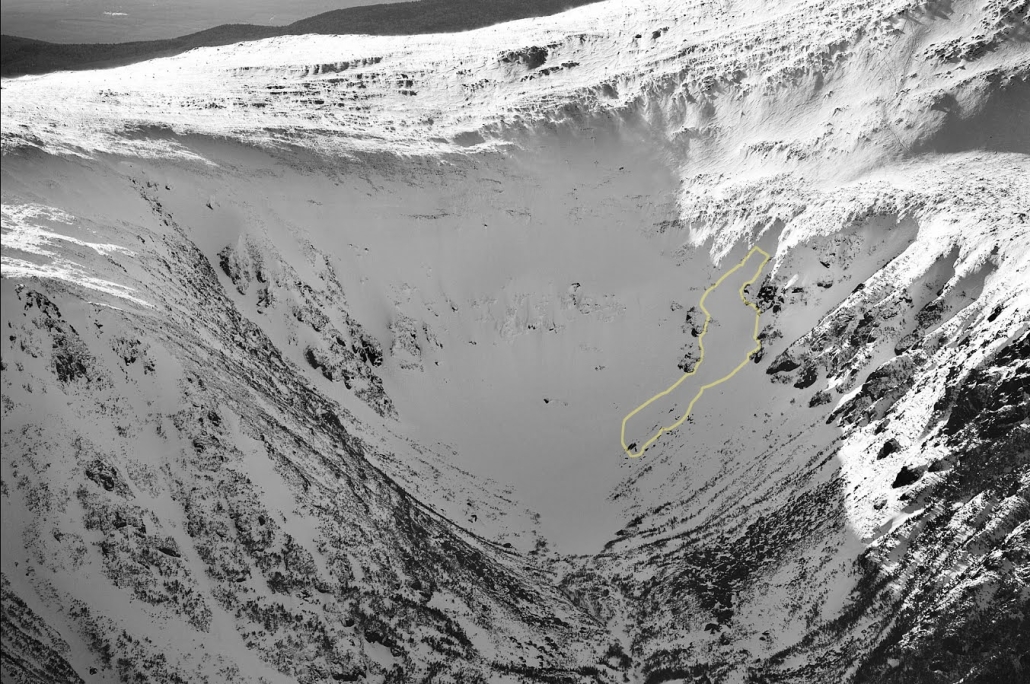

On the morning of March 4, 2022 around 11:30am a skier triggered an avalanche while skiing Sluice in Tuckerman Ravine. They were caught, carried about 300 feet, not buried, and uninjured, coming to rest on top of the debris pile above “Lunch Rocks.”

Avalanche

The skier accessed the top of Sluice by climbing up Right Gully and traversing to the top of the ski line before descending.

The hard slab avalanche was triggered at a thin spot in the slab near the Sluice icefall, partway down the line. The fracture propagated roughly 40 feet above the skier and 75 feet laterally in each direction. This avalanche was D2, R3 in size with a maximum crown depth of 3 or 4 feet. The width of the avalanche was estimated at 150 feet with an estimated track length of 450 feet. In the track of the avalanche, areas of frozen bed surface were exposed, indicating that the avalanche stepped down to the February 22nd rain crust and entrained slabs formed earlier that week. The crown line wrapped around the ridgeline towards The Lip and in the other direction toward the mouth of Right Gully.

Snowpack and Weather

Shortly after the incident, forecasters performed instability tests nearby on a similar elevation and aspect which yielded reactive results on a weak interface around 45cm below the snow surface. Test results were ECTP10 and ECTP11. Slab hardness was 4-finger with a similar hardness below the weak interface. Multiple other parties reported reactive and touchy sensitivity at the same weak interface buried between 30 – 50cm below the snow surface.

The setup for this avalanche problem and this incident began on February 22nd when the summit of Mount Washington reported 0.78 inches of rain with an additional 0.32 inches of rain the following day. A subsequent drop in temperatures refroze the snow surface into a very hard crust layer in the days following this weather event. Over the next 10 days leading up to March 4, a total of 25 inches of snow equaling a total of 2.38 inches of water was reported on the summit. Prevailing west and northwest winds loaded this snow and drove wind slab formation over this same period. Many natural avalanches were observed in this 10-day period, with several slopes on similar aspects avalanching multiple times and becoming re-loaded with wind-blown snow.

A break in snowfall on February 28th allowed wind and sun to slightly stiffen the current snow surface, creating a thin density change and the future bed surface for avalanches over the next 3 days. On March 1st, 2nd, and 3rd, a total of 10.3 inches of snow fell on northwest winds and continued slab formation. Initial snowfall after the 28th fell on calm winds before wind speed and snowfall gradually increased, creating a subtle strong-over-weak character to this slab.

Visibility and sun returned on March 4th and large recent avalanches on Center Headwall and The Lip in Tuckerman Ravine became visible at sunrise. Slab failure and propagation was consistently being seen on the aforementioned thin mid-slab interface where there was a slight change in density within the greater wind slab. Generally, this was found 30 – 50cm below the snow surface, but was buried deeper in wind-sheltered pockets of terrain, like Sluice.

On March 4th, the avalanche danger was CONSIDERABLE at middle elevations and MODERATE at upper elevations for the Presidential Range. The primary avalanche problem was wind slabs on northeast-facing through southwest-facing slopes with a likelihood of possible and a destructive size estimate of D2. Sluice is a southeast-facing slope with an average slope angle of about 40 degrees that sits within the middle and upper elevation bands. Click here for the full March 4th avalanche forecast.

Analysis

This avalanche is a great example of thin spot triggering with effective propagation to slopes above and around. Like in this case, if a crack is able to propagate above your head high on the slope above you, it can be hard or impossible to escape the debris flow.

The skier writes “I skied 10 slow, smooth, short radius turns which felt firm and stable. On the 8th turn, propagation took place 40’ behind me and I soon felt the steep slope give way underneath. I proceeded to point my skis straight to ride it out but by now was fully engulfed by the avalanche while being swept 350’ below. During the slide I was fortunate to remain on the top of the snow before finally coming to a sitting upright stop in a soft pile of snow debris with one ski on and the other a few feet behind.”

They go on to say, “On March 4th, my decision making failed and I should have known better. The forecast stated it clearly to ‘not rule out the possibility of triggering a large, firm slab – all it takes is finding a weak spot over a rock to get it sliding.’ I underestimated the weaknesses of this slab in correlation to current conditions and features.”

Additionally, this accident highlights the high degree of spatial variability that is associated with the Presidential Range forecast area, largely driven by high wind and steep avalanche terrain. Our direct-action avalanche cycles offer heightened danger shortly after snow and wind events, but continuous high winds after the initial storm often lead to stubborn slabs that are hard to trigger. This seems to have been what the skier was expecting, as this is a common scenario in this zone. However, in this case, slight nuances of loading patterns and layering subtleties within the slab as described above meant that higher slab sensitivity persisted longer than what longtime local skiers might be used to.

Lastly, making the decision to ski solo decreased the skier’s margin for error even further by not having a partner that could extract them in case of a full burial, provide care in case of injury, or act as another voice in the decision making process. At face value, skiing solo should not be considered a mistake, but rather a choice that can compound consequences of an accident in an avalanche or injury scenario.