Summary:

At about 11:30am on Saturday, December 9th, a backcountry skier triggered an avalanche while descending Airplane Gully in the Great Gulf Wilderness. The skier was caught, carried, and not buried, but they sustained serious injuries during the fall. The skier’s partner and a bystander were able to effectively provide assistance and first aid until rescue services arrived. The current General Avalanche Information from the Mount Washington Avalanche Center (MWAC) for December 9th warned of “isolated areas of unstable snow at middle and upper elevations which could avalanche from the weight of a person.”

Backcountry Avalanche Forecast:

On December 9, MWAC had published a current General Advisory. The bottom line stated, “Watch out for isolated areas of unstable snow at middle and upper elevations which could avalanche from the weight of a person. Use proper route finding to avoid these areas and evaluate the snowpack carefully when in steep terrain where snow has collected. Falls in steep terrain can be consequential because of the hazards still present in the early season snowpack.”

Snow, Weather, and Avalanche Events:

*Avalanche Forecasters were not able to access and analyze the Airplane Gully avalanche after the incident. This assessment is generalized and based on first hand accounts, data shared from the reporting party, and photos.*

The general state of the snowpack on December 9th at middle and upper elevations was thin, disconnected, and developing – typical for this time of the year. A significant snowstorm on December 3rd and 4th brought almost 18 inches of new snow to the Mount Washington Summit. Over the following 5 days, much of this new snow was redistributed by dominant northwest winds onto lee terrain. During and immediately post storm, multiple small natural avalanches were observed. An increase in wind on the 7th formed reactive wind slabs in isolated areas. A notable human-triggered avalanche occurred in the Tuckerman Ravine area on December 8th, with other small, natural avalanche activity observed in Tuckerman Ravine and Gulf of Slides. These avalanches were size D1 – D2 hard slabs, with tapered crown lines ranging from about 6 inches to about 2 feet in depth, and limited in width. A similar snowpack setup existed in the steep east and northeast-facing terrain of the Great Gulf Wilderness, where the accident occurred. Photos confirm the variable nature of these wind slabs with an overall very shallow snowpack in the Great Gulf. Additionally, the Mount Washington summit recorded warming temperatures on the 9th with a high of 37 degrees F. This warming likely contributed additional load on any existing slabs.

Events Prior:

On the morning of December 9, a team of two backcountry skiers (Skier 1 and Skier 2) made a plan to ascend alongside the Mount Washington COG Railway, and assess the conditions of Airplane Gully in the Great Gulf Wilderness as a potential ski option. Depending on the group’s assessment, they would decide to either ski Airplane Gully, or descend back down the COG Railway if they felt avalanche risk levels were too high.

When they arrived at the entrance of Airplane Gully, they began taking visual observations, making snowpack assessments and comparing the information they were collecting to the information they gathered from MWAC over the previous days. Together, they completed column tests and an extended column test at the top of the line which showed no clear signs of instability. They had brought a ski-mountaineering rope and talked about making a belayed ski cut, but decided against it after completing stability tests and making visual observations of the terrain below.

While the team was assessing conditions, a solo skier arrived to ski the same line. This person briefly asked if they were going to ski the line before dropping in seemingly without making snowpack assessments. Skiers 1 and 2 watched as the solo skier descended and didn’t see any signs of snowpack instability.

This additional information increased the team’s confidence in snowpack stability and they decided to ski Airplane Gully. The team managed the risk and exposure of the first section by skiing one-at-a-time, skiing in pitches by stopping in a protected area to wait and watch the other partner descend, and using radios as communication tools. Skiers 1 and 2 regrouped in a sheltered area near the intersection of the Spacewalk traverse, around 5200 feet. After regrouping and confirming good stability on the first section, they noticed the solo skier climbing back up the gully. They decided to wait for this person to reach them before continuing in order to limit the risk to the person below and also to obtain additional information about the snowpack lower down.

Accident Summary:

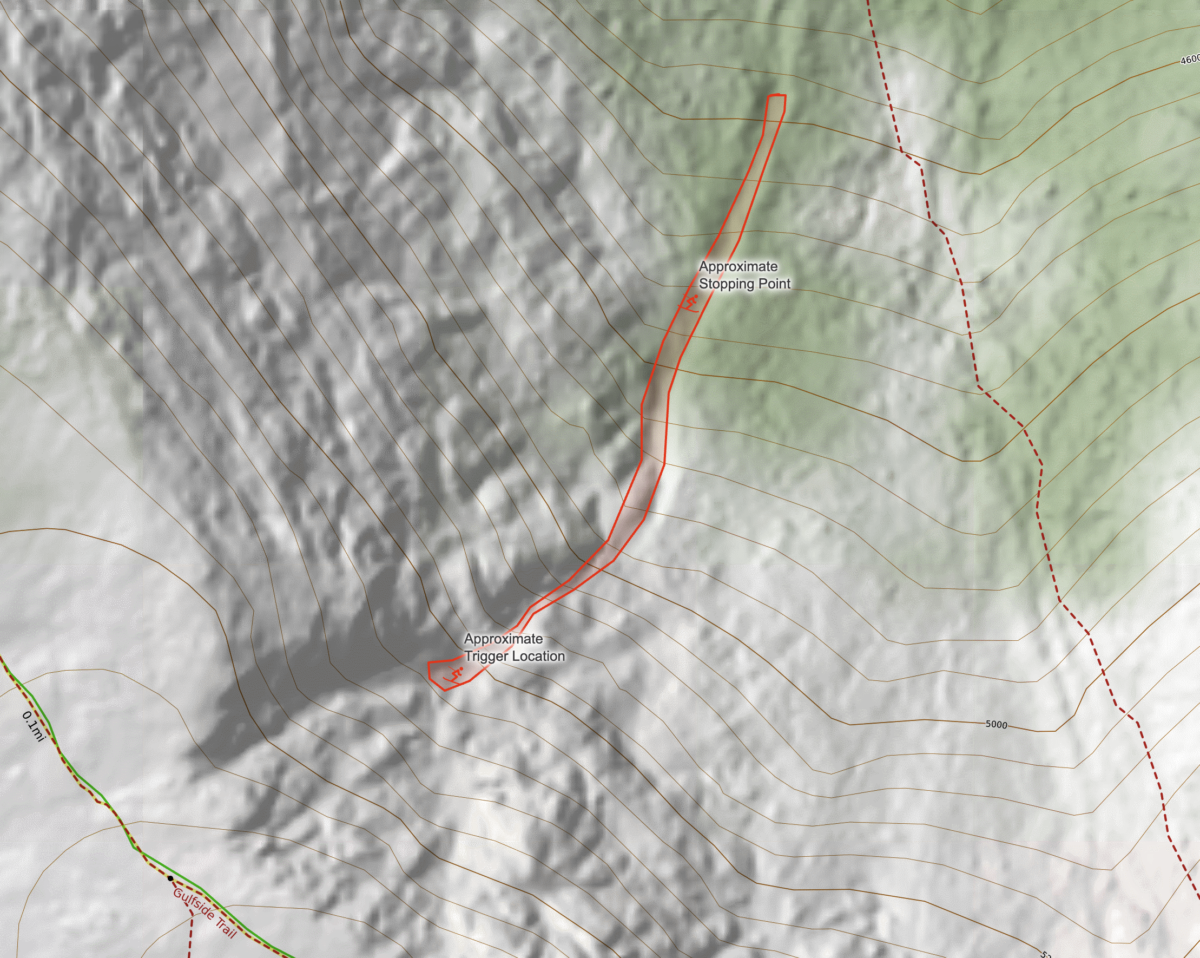

Skiers 1 and 2 talked with the solo skier and confirmed there were no signs of instability after the first ski descent. Skier 1 then began skiing the next section, making a few turns before triggering a ~15 foot wide hard slab avalanche, capturing and carrying that person down the slope. During the fall, other small avalanches were sympathetically released from disconnected pockets of snow, contributing to the overall amount of snow falling down the slope. Skier 1 was carried a total of about 500 vertical feet down the gully before coming to rest, unburied, at about 4700’ near the top of the Airplane Gully runout zone.

Rescue Summary:

While being carried in the avalanche, Skier 1’s binding did not release, causing an open fracture of the tibia and fibula. They immediately noticed the injury, communicated their condition to Skier 2 over the radio, and called 911. Skier 2 and the solo skier bystander were able to safety descend to Skier 1 and provided immediate assistance which included activating an InReach emergency satellite device, digging a platform, removing the injured skiers ski, stabilizing the injury, controlling the serious bleeding, and keeping the skier warm. The team’s medical training and supplies were crucial in this effort.

After over 4 hours, with coordination between NH Fish and Game, NH Army National Guard, Mount Washington Avalanche Center, and Mountain Rescue Service, a NH Army National Guard helicopter was able to safely extract the injured skier via short haul and transport Skier 1 to the hospital.

Avalanche Statistics:

Type: Hard Slab

Trigger: Skier, unintentional

Aspect: Northeast

Slope Angle: 40 degrees

Size: R2, D2

Elevation: 5200 feet

Sliding Surface: New / Old Interface

Vertical Fall: 700 feet

Width: ~15 feet

Discussion:

The team was well-prepared for this objective. They both were carrying avalanche rescue equipment, technical ski-mountaineering equipment, first-aid and medical supplies, and emergency communications tools. Additionally, both skiers have spent significant time in ski mountaineering terrain, have avalanche education, have emergency medical training, and had read and understood the current MWAC avalanche information and recent observations of avalanches in other areas.

This incident underscores a few important insights relating to travel in the Presidential Range avalanche terrain.

First, it highlights the high degree of spatial variability that our range is known for. Conditions assessed at the top of a terrain feature often yield different results than the conditions found just a few hundred feet down the slope. These subtleties have caught many experienced backcountry enthusiasts and professionals off-guard over the years and contributed to several accidents. In the early season with a very thin snowpack, this variability can be even more pronounced. Additionally, as we saw in this case, one person skiing a slope without incident, does not guarantee a stable snowpack.

Secondly, this incident highlights the severe implications of even a small avalanche in technical terrain and early season conditions. Many avalanche run-out zones (especially in the early season) are littered with rocks, ice, and vegetation that can cause trauma upon impact. This often makes the fall equally or more dangerous than the actual avalanche itself.

Thirdly, we should all make a point to inspect and tune up our backcountry knowledge, ski gear, and safety equipment. In this case, a failed binding release caused a very negative outcome for the skier caught in this avalanche. If the binding had released, it’s entirely possible the skier would not have been injured and would have had the ability to evacuate on their own. Their level of medical training and carrying a well-stocked medical kit was instrumental in the outcome of this accident. Access to trauma supplies, basic splinting supplies, emergency shelters, and personal levels of training, greatly improved the prognosis for those involved in this accident.

Finally, it’s important to remember that we can seemingly be doing everything right and still have an avalanche accident. We gain experience, take courses, read the avalanche forecast, make slope-specific assessments, and practice good terrain management to reduce our risk in the mountains, but we can never fully eliminate that risk. We also let a variety of information influence our decision making. The injured skier mentioned that if the solo skier hadn’t come along and skied the slope without incident, they were ready to make a conservative decision to turn around and ski down the COG.

MWAC would like to thank the skiers involved in this incident for their openness and honesty about their accident with the hope of public awareness and education. We wish Skier 1 a speedy recovery.