SYNOPSIS:

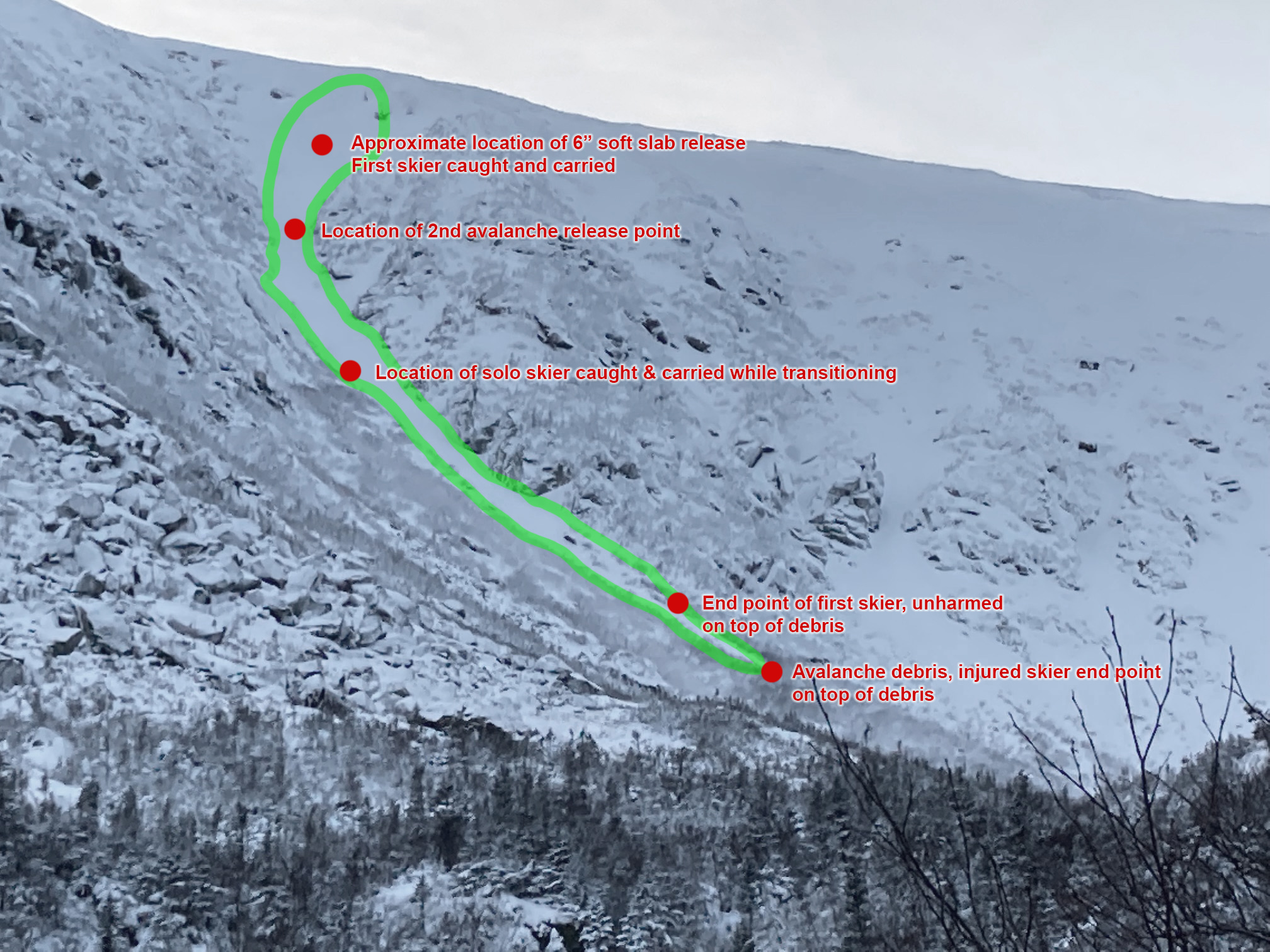

On December 5 at approximately 12:00 pm a skier triggered a shallow soft slab avalanche near the top of Left Gully. The skier was caught and carried, and a short distance later triggered a 2nd, larger avalanche. The skier was carried 800 vertical feet, unharmed and landed on top of the snow at the mouth of the gully.

At the same time, a solo skier was half way up the gully transitioning from climbing to skiing when hit by the avalanche. The skier was carried downhill 450 vertical feet, hitting exposed rocks along the way with serious injuries the result, coming to a stop on top of the avalanche debris pile well below the entrance to the gully. After medical needs were addressed, the patient was placed in a rescue litter and transported to an ambulance waiting at the trailhead by a group including Forest Service Snow Rangers, Harvard Cabin Caretaker, the two other skiers involved from above and several bystanders. The rescue effort involved 9 people and 5 hours.

EVENTS:

On Sunday December 5, winds were light in Tuckerman Ravine, temperatures seasonably cold with poor visibility near the top of the ravine. In the 5 days prior to December 5, 1 to 3” of new snow was recorded on the summit each day, with varying wind speeds from the west and northwest. It was reported that several parties were climbing or skiing in the ravine that day.

Late morning, two skiers climbed to the top of Left Gully, evaluating the snowpack using hand-shear tests along the way. They found softer snow than expected but no obvious signs of instability. Near the top where the constricting rock walls end and the gully opens up, they noted a shallow pillow of wind drifted snow (6” deep maximum) to the right, continuing up and left to avoid the hazard. They transitioned to skis at the top with poor visibility. Both were prepared with avalanche beacons, shovels and probes.

While the two skiers at the top of the ravine were preparing for the ski down, a solo skier reached his highpoint, climbing approximately half way. He stopped, took off his pack, and removed his skis attached to his pack. This solo skier was unaware of the two skiers above preparing to descend. His avalanche rescue beacon was turned on well before he entered avalanche terrain.

Back at the top of the gully, the two skiers made a plan to ski the steeper entry on the right, appropriately skiing one at a time. When the first skier descended, the soft slab released, pulling the skier off his feet and he was swept down with the debris. Soon after, when the skier and debris reached the narrow constricted portion of the gully, a larger, deeper avalanche was triggered with a crown line that ran wall to wall, approximately 20-26” inches at the highest point. The avalanche was large enough to bury, injure, or kill a person and encompassed a medium-sized portion of the whole slide path (D2-R3). This skier was carried approximately 800 vertical feet by the avalanche, coming to a stop at the entrance of the gully near a rock buttress separating Chute from Left Gully. He was unhurt, and on top of the snow.

At the same time, the solo skier had not yet removed his crampons when he was caught by the same avalanche and carried approximately 450 vertical feet, encountering rocks along the way, arriving at a point further downhill than the first skier. He was on top of the snow with serious injuries requiring immediate medical attention.

The remaining skier above descended on skis with continued poor visibility looking for clues to help find potential victims. He quickly found his partner (the first skier), and the injured solo skier. A beacon search of the debris was conducted to rule out additional buried victims of the avalanche. The two skiers moved in to help the solo skier, managing injuries when the Harvard Cabin Caretaker arrived on scene immediately notifying USFS Snow Rangers using a radio. After a patient assessment, and continued management of medical needs, the patient was packaged in a rescue litter. A Snow Ranger arrived on scene to direct transport. A team consisting of Snow Rangers, Harvard Cabin Caretaker, the two skiers from above and several kind bystanders spent the next four hours carrying/dragging the patient litter sled over rocks and snow to an ambulance waiting at the trailhead arriving at approximately 5:30 pm.

ANALYSIS:

If we have new snow and wind you are likely to find slabs of drifted snow with the potential to be unstable, resulting in an avalanche when additional load is added such as a skier or climber. This can and does occur before the Mount Washington Avalanche Center issues a daily avalanche forecast with a hazard rating. Due to shallow snow cover overall, the current terrain options for skiing are limited. Left Gully has been a very popular destination for skiers over the last few weeks with snow coverage top to bottom. The gully is long, constricting with no options to escape until the bottom opens up. With poor visibility it may be impossible to see if anyone is above or below, adding an additional hazard beyond the snowpack alone. Early season excitement, limited terrain to ski, solo skiing, shallow snowpack with rock filled run-outs, poor visibility and recent wind drifted snow are all factors that contributed to this unfortunate event.

It’s worth remembering that we have a long winter ahead with (hopefully) plenty of snow. Slow down, think carefully about decisions you make, and consider that your actions may also impact others. An old saying goes something like this: Experience is a brutal teacher. The test comes first, then the lesson.